Blog

Holocaust Survivor Speaks to Southmont Students

By Joe LaRue, joe@thetimes24-7.com

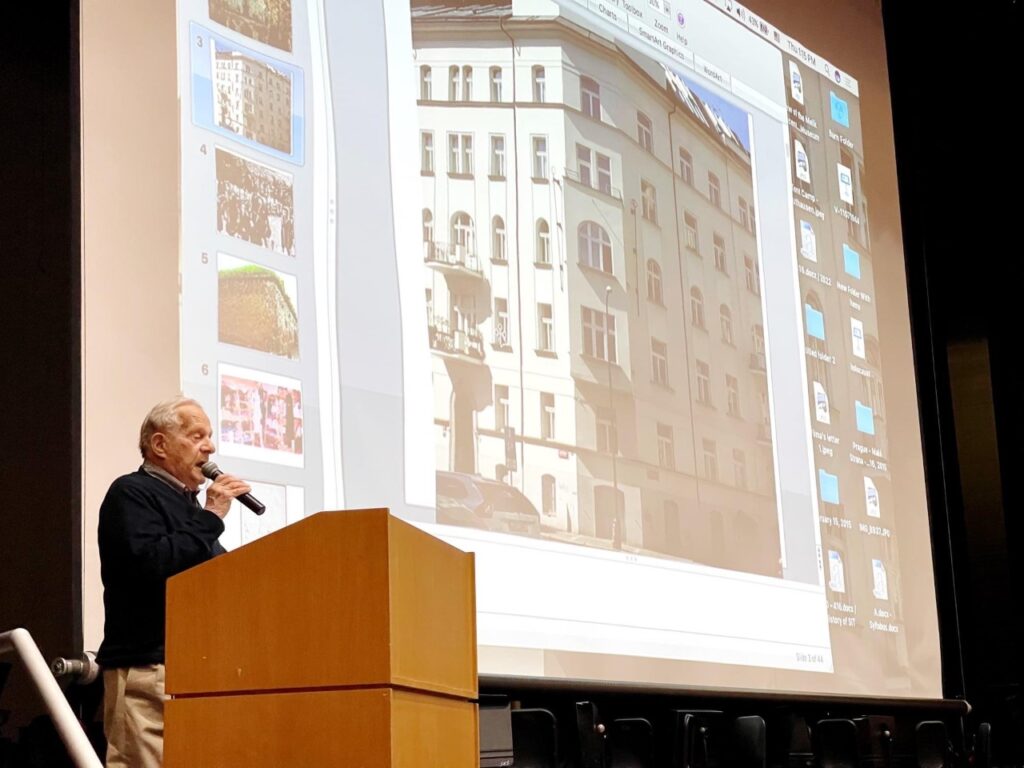

Standing behind the podium in Southmont High School’s auditorium, packed to the brim with high school and junior high school students, Holocaust survivor Frank Grunwald spent an hour on Thursday recounting the unimaginably horrific events of his childhood. But it was an hour that those students will never forget.

Thursday was Yom HaShoah, or Yom HaZikaron laShoah ve-laG’vurah as it is known in Hebrew. Yom HaShoah is International Holocaust Remembrance Day and is Israel’s remembrance day for the victims of the Holocaust, though it is celebrated around the world. In honor of that day, Southmont High School invited Frank Grunwald to come and speak about his experiences during the war.

It is difficult to describe one’s expectations going into a presentation like this, but whatever those expectations are, they will inevitably fall far short when faced with Mr. Grunwald’s story, in his own words.

Frank Grunwald speaks to a packed auditorium at Southmont High School on Yom HaShoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day.

Frank was 6 years old when the Nazi’s marched into Czechoslovakia in March of 1939. He recalled his early years, living with his mother, father and brother in the apartment building in Prague his grandparents owned. His grandparents lived on the fifth floor and Frank’s on the second. His father was a physician.

In the years since his immigration to the United States in 1951, Frank has become known for his love of art and music. That love burgeoned when he was a young boy, he recalled, and he, “remembered sneaking into his father’s office to steal insurance forms to draw and sketch on because I never had enough drawing paper,” he told the assembled students.

But the joys and trivialities of life the Czech capital vanished with the arrival of the Nazis. “The German invasion caught us completely by surprise,” he said. “My brother and I we were walking one day and ran into a German gun emplacement with one gun and one German soldier. He picked me up and put me in the seat where he had been sitting. And that was how we found out Germany invaded.”

Despite the innocuous nature of his first encounter with a German soldier, Frank made clear that drastic changes happened practically overnight. All over Prague, anti-Semitic propaganda went up within days and signs barring Jews from restaurants, theaters and businesses were omnipresent.

Frank spoke at length of his apparent lack of Jewishness; his parents were not practicing Jews, and he and his brother were not raised Jewish. “My mother gave us a religious upbringing, but it wasn’t Jewish,” he said. “It was more of a universal religious raising. She taught us how to respect others, to treat others the way we wanted to be treated.”

But the Germans in Prague had no regard for such distinctions. Within months of the occupation, Frank’s father had lost his job, Frank and his brother had been kicked out of school and the family had lost their apartment, ending up in a crowded, cramped apartment on the other side of the city.

In 1942, the family was ordered to report to a train station for ‘relocation;’ they were shipped to the notorious Theresienstadt Ghetto in Terezin, a town in western-Czechoslovakia. Upon arrival, Frank and his brother were separated from their parents and moved to an old school converted into barracks. There, they received minimal education, space was crowded and they were packed hundreds to a room.

While in Terezin, Frank came to the realization that the ghetto was not their destination; instead, it was a holding place, from which they would be moved further. He recalled the moment he found out, saying, “A young boy living in my room at the school came in upset. When we asked why, he told his grandmother was in a coma.”

“She had tried to kill herself,” he said, “because she found out that she had been scheduled to be deported to a camp. And that was when I realized what this place was.”

Frank and his mother Vilma.

In December of 1943, the Grunwalds were ordered to the train station in Terezin. Their time for deportation to a camp had come. But Frank’s family was not told where they were going.

“They put us in a train, in December, and we traveled for two days with no food or water,” he said. “When we finally stopped and they opened the doors, it was nighttime. We were greeted with floodlights, barking dogs and guards shouting at us ‘Get out! Get out!’” They had no idea where they were.

They had been sent to Auschwitz, the infamous Nazi death camp in Poland alone responsible for the deaths of over 1 million people.

But as Frank described it, the trainload of new arrivals that he was part of were some of the lucky ones. “Instead of immediately being put through selection, we were loaded into trucks and taken to the Czech family camp.”

The selection Frank referred to was a process new arrivals at the camp typically went through. One by one, every new arrival stood in a line and underwent inspection. Those sent to the right were herded to one of the many sub-camps to be put to work; those sent to the left were sent to the gas chambers to be killed immediately.

But at this point, word had begun to spread through European countries of what was taking place in these camps. In order to dispel rumors, Frank, his family and their follow new arrivals from Terezin were forced into a separate sub-camp for six months. There, Frank said, “we were forced to work, take photographs and send postcards to family or friends that said only positive things.”

On July 6, 1944, however, the ruse was up for Frank and his compatriots. They were taken back to the arrival point and put through selection. Initially, Frank recalled, he and his brother, four years older and born with a congenital leg defect, had been sent to the right. “I was standing in a group of 200 or 300 boys, on the right, and I looked over and saw a group of 95 or 96 boys standing to the left.”

But a kapo, a prisoner assigned to oversee other prisoners, who had been in charge of the camp Frank and his family had previously been living, intervened. Kapos were usually non-Jewish German or Austrian prisoners, often in camps for crimes or being politically opposed to the Nazis, and were in place so that the camp guards did not have to directly deal with the Jews.

This kapo, named Willie Brachmann, had picked Frank to be his messenger and errand-boy. When he saw Frank on the right side of the selection table, Frank recalled, “He came over, grabbed me roughly, and pushed me over to the left side.”

“I looked back over and saw my brother still on the right, and I was on the left, and I knew what was going to happen. And he was led away with my mother.”

Five days later, Frank’s mother and brother were gassed.

The packed auditorium at Southmont High School on Thursday, where Frank Grunwald shared the story of his survival of the Holocaust. On stage, Frank tells the assembled students about his pre-war life in Prague, the Czech capital, where his father was a physician and Frank first discovered his love of art.

At this point in the presentation, Frank, who was narrating along to images on a series of PowerPoint slides, stopped on a grainy picture of an old letter written in Czech. He told the story of it, and throughout his recounting, you could hear a pin drop.

The letter was from his mother. She had written it in the minutes before her and Frank’s bother were taken to the gas chamber to be killed. It was addressed to Frank’s father. He read out some of the excerpts, but the full text of the letter is as follows:

“You, my one and only, my dearest. We are locked in in our block, waiting for the dark. Margetha Braun and I went to Willy’s, who did not leave us with a moment of doubt. With Jenda we at first thought of hiding, which we did, but then we dropped the idea on the assumption it would be hopeless. The infamous trucks have arrived and we are waiting for it to begin. I took five bromides, after this exhausting and unnerving day I am somewhat dazed but completely calm. My dear Jenda is also admirable.

You, my one and only, my dearest, do not blame yourself in the least; it was our fate. We did what we could do. Remain in good health and remember my words that time heals everything—if not completely, then at least in some measure. Take care of that little golden boy—and don’t spoil him with all your love.

May you both remain in very good health, my two dear golden ones. I will be thinking about little Walter—do you remember how I once said his passing would ease our way? And then, I will be thinking only of you and Míša (Frank’s birth name).

Live well; we have to get on board. Into eternity,

Your Vilma”

In desperation, she gave the letter to a guard and asked him to deliver it. Frank recalled that, “he was not an SS soldier, just a regular military guard, so he must have had some compassion. He brought it to my father the next day.”

Frank’s father carried it throughout the year. After the war, Frank would not look at the letter for years. When his father died in 1967, Frank found it among his possessions, aged and yellow. He still hadn’t read it, but finally took the opportunity to do so. For decades after, he kept the letter hidden from the world, including his wife Barbara, until finally, in 2015, he passed the letter along to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.

In recalling his choice to give the letter to the museum, Frank said, “First, I was going to give them a copy of the letter, and I decided that the original needs to be preserved for a long time and exposed to lots of people, which it would be in a museum.” He went on to say, “I would be better off making a copy of it, keeping it for my family, and letting the original be available to the public.”

In an interview with The Indianapolis Star in 2018, Judith Cohen, chief acquisition’s curator for the Holocaust Memorial Museum, spoke of the uniqueness of the letter that Frank’s mother Vilma wrote.

“”I’m always reluctant to say it’s the only such document ever created,” Cohen said, “but to the best of our knowledge it is — it is the only one we have ever seen. Auschwitz, in the moments before gassing. In the extermination camps it was almost impossible to write material that was preserved.”

The full interview can be read at https://www.indystar.com/story/entertainment/2018/04/28/into-eternity-she-did-not-survive-holocaust-but-her-words-did/551071002/.

In the months after the death of his mother and brother, Frank’s father was deported out of Auschwitz. The two would not reunite until after the war. Frank, on the other hand, endured several long death marches. As the Russian Army advanced through Poland in the autumn and winter of 1944, Frank and his fellow Auschwitz inmates were sent on a death march to clear the camp and avoid discovery by the Russians.

For two days in the midst of winter in January of 1945, Frank and his inmates marched for miles through the cold, without food and water. Frank spoke of the second day, when he began hallucinating from exhaustion and starvation. “As we marched, in the ditch on the side of the road, all I could see were dead bodies. I was with some Polish dentists, and I said, ‘I cannot go on, I am too tired.”

But the Polish dentists forced him along, he said, and he made it to the train station. From there, they were sent some 200-plus miles to Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria. When they arrived, Frank said, “It was a disaster of a camp, extremely dangerous, full of disease and starvation.”

After six days in Mauthausen, Frank and his fellow prisoners were taken to a small sub-camp of Mauthausen called Melk, where they remained for three months. Then, in April of 1945, as British and American soldiers rapidly moved through Austria in the late stages of the war, Frank again was sent on a death march. They returned to Mauthausen, this time sleeping in tents with mud floors for four days.

After this, Frank endured his final death march, some 29 miles, from Mauthausen to Gunskirchen, another sub-camp of Mauthausen, where some 15,000 emaciated prisoners were left to die in the final days of the war. On May 4, 1945, just days before VE day, Gunskirchen was liberated by troops in the 71st Infantry Division and the segregated 761st Tank Battalion. Frank’s horror had ended.

After the war, he spent some months in a holding facility. After one of the boys fled the facility and returned to Prague by train-hopping, he remarkably found Frank’s father and informed him of his son’s status. His father, Kurt, immediately traveled and gathered his son.

They spent several years in Prague before fleeing the communists in 1949. They spent two years in England before moving to New York City in 1951. There, Kurt became a general practitioner and Frank got a degree in Industrial Design from the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. After 45 years at GE and several other companies, Frank retired in 2002. He became a guest lecturer at Purdue and a speaker on his experiences in the Holocaust. He is married to Barbara Grunwald, and they have two children and currently reside in Indianapolis.

Frank spoke about how much those events are still with him, saying, “It’s there all the time; unfortunately it never leaves me.”

“I heard someone, one of the Polish prisoners say, recently actually in an interview, that ‘once you live in Auschwitz, then after that you have two lives. One life is Auschwitz and one life is your other life. And that is very true.”