Blog

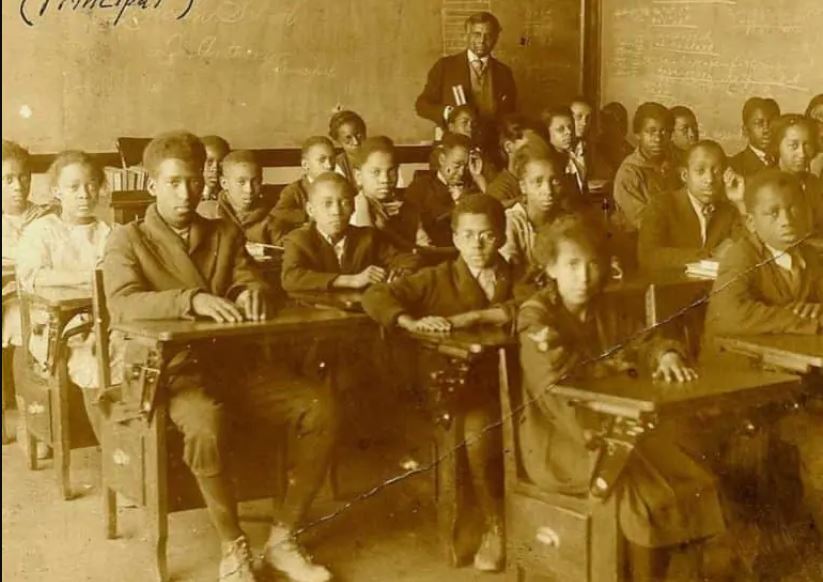

The Lincoln School For Colored Children

EDITOR’S NOTE: In 1881 Crawfordsville School Trustees ordered a school be built at the southwest corner of Spring and North Walnut Streets to serve black students in grades 1-8. Once graduated, the students attended the integrated Crawfordsville High School. This site accommodated the vast majority of black families living in Crawfordsville’s north end. Trustees purchased the lot in September 1881 for $2,000. On Dec. 3, 1881, Hinckley and Norris won the contract to build the building for $6,400. The architects designed a plain two-story red brick structure with playgrounds for all the black children who resided in that area. Lincoln School officially opened in September 1882 with 42 students. When the black population moved to the east end to work in the factories, Lincoln Building 1 was renovated into Horace Mann, and Lincoln Build 2 was opened on East Wabash Avenue. That building became Lincoln Rec Center and was demolished in 1981. This project began as a project historical research project to honor all those individuals who went to school in separate and unequal facilities as the law dictated.

Dr. Robert Anthony

1866 to 1841

Educator from 1918- 1931

Robert L Anthony was born on 28 November 1866 in Fairfield, Ohio, to Mark and Melissa Young Anthony, both natives of Mississippi. Mark was a barber, and Melissa was a homemaker.

Robert had two brothers and two sisters, and the family spent the children’s childhood living in Ohio and Illinois.

Robert graduated from Iowa State Normal School, Wilberforce University, Cornell University, and Eastman College. After graduation, he was a principal at schools in Olmsted, Illinois, Cairo, Illinois, and Indianapolis, Indiana. He eventually taught in the Business Department of Simmons College of Kentucky in Louisville.

On 28 June 1893, Robert married Carrie B Gaddie of Louisville, Kentucky, daughter of Reverend Daniel Abraham Gaddie and Julia Pearce Gaddie. By 1900 the couple was living in Southeastern Illinois with three children, Frank, Julia, and Esther. Both Robert and Carrie taught school. On 27 March 1906, Robert and Carrie lost their 12-year-old son Frank to septicemia, and on 23 August 1913, lost their 14-year-old daughter Esther to tuberculosis.

Robert’s teaching career then took the family to Vincennes, Indiana, and to Knox, Indiana. While there, three additional children, Naomi, Robert, and Helen, were born. By 1920 the family had made their way to Louisville, Kentucky, and were living at 939 Clay Street. While there, they added daughter Minnie to the family.

Bethel AME Church history suggests that Robert migrated to Crawfordsville with his mother, Melissa. Listed as a podiatrist, he envisioned establishing the Roosevelt Memorial Hospital for Spanish-American War veterans and Black residents that were not allowed in city hospitals. In 1920, he purchased the large frame house at 304 Covington Street and searched for funding from the Bethel AME Church and local Black social lodges who agreed to furnish the rooms. Local White doctors agreed to see patients until the hospital got on its feet. The hospital did not turn a profit, but stakeholders hoped it would become self-sustaining. By 1921, according to the school’s yearbook, Crawfordsville High School’s Sunshine Society members were delivering cheer baskets to Roosevelt and Culver Hospitals. Roosevelt Memorial Hospital disappeared from city directories after 1928. Culver Union Hospital was treating Black patients by 1929 when it became a public hospital. Unfortunately, Robert’s mother died, and so did his vision. Once Roosevelt closed, Bethel AME Church history suggests Robert converted the home into apartments.

Robert taught grades five through eight at Lincoln School from 1918 through 1931. Students claimed “he fell asleep often in class, giving us plenty of opportunity for noiseless mischief.” Crawfordsville resident Jerry Eubank remembered Robert exceptionally well as he “wore a blazer with candy in his pocket which he handed out to students as he walked around. Students were expected to say “good afternoon Dr. Anthony” or something of the sort, and he would give them a piece of candy.” Jerry recalled when Robert taught sixth grade, “boys would be boys and were clowning and carrying on, so he told us one day, “I’m here to teach you guys. So if you don’t get it, it’s all your own fault”. According to other former students, Robert could “sit and recite Shakespeare without opening a book, line for line. He had a remarkable remembrance. I can still see him stomping around; he was lame, reciting The Charge of the Light Brigade. You could sit there with your book open, and he wouldn’t miss a word. How he could remember all of it, I’ll never know.”

Former student Maxine Burdette remembered that Robert was one of the few teachers who lived in Crawfordsville. She recalled, “Anthony looked more Indian than he did anything else. He was copper colored and heavyset. He was a very good teacher and a very smart man, but he would let the kids go out for recess, and if you wanted to come in, he just sat and took a nap. Dr. Anthony didn’t have supervised playgrounds. He was a very good teacher, but when we went to junior high school, we had a real hard time in some subjects because he had not taught us the things we should’ve known to enter the White school”.

Robert’s name disappears from all Crawfordsville school records after the 1930-1931 school year. The 1940 census indicates that Robert and Carrie were back together at the Clay Street home in Louisville, Kentucky, where Robert again became a professor.

On 9 May 1941, Robert died of diabetes. Carrie died on 18 December 1946 of arteriosclerosis.