Blog

The Lincoln School For Colored Children

EDITOR’S NOTE: In 1881 Crawfordsville School Trustees ordered a school be built at the southwest corner of Spring and North Walnut Streets to serve black students in grades 1-8. Once graduated, the students attended the integrated Crawfordsville High School. This site accommodated the vast majority of black families living in Crawfordsville’s north end. Trustees purchased the lot in September 1881 for $2,000. On Dec. 3, 1881, Hinckley and Norris won the contract to build the building for $6,400. The architects designed a plain two-story red brick structure with playgrounds for all the black children who resided in that area. Lincoln School officially opened in September 1882 with 42 students. When the black population moved to the east end to work in the factories, Lincoln Building 1 was renovated into Horace Mann, and Lincoln Build 2 was opened on East Wabash Avenue. That building became Lincoln Rec Center and was demolished in 1981. This project began as a project historical research project to honor all those individuals who went to school in separate and unequal facilities as the law dictated.

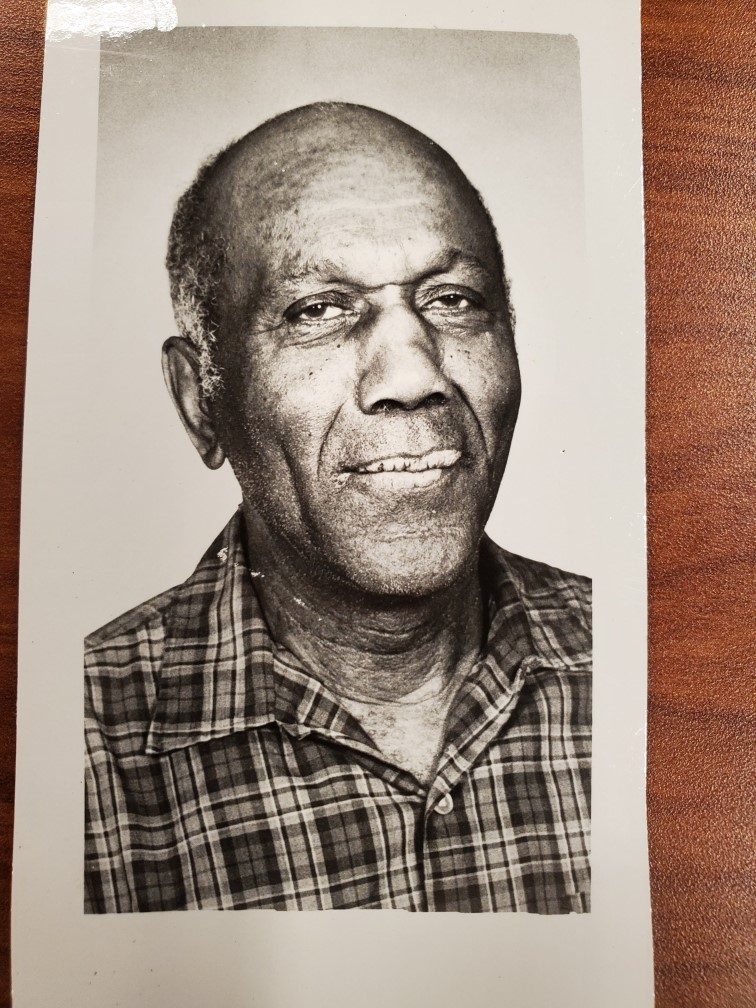

Clarence Norwood “Sam” Churchill

1906- 1985

Clarence was born on 26 August 1906 in Crawfordsville, Indiana, to William and Denia Richey. Bethel AME Church history suggests that “his mother was an ex-slave born in Canada, who was the neighborhood’s midwife before Blacks were allowed treatment in local hospitals. Her knowledge of herbal medicine was of special note; she used smashed eels for shingles”. Denia’s cousin, George W. Thompson, was a schoolteacher at Crawfordsville’s Lincoln School for Colored Children.

Clarence had good memories of his childhood. When Clarence was born, the family lived on Harrison Street. “All I did was run with the White kids all the time, and played around and went to their homes. They would come to my house. My mother would feed them, and their mothers would feed me. We went swimming and fishing, catching catfish, carp, sunfish, bluegill, and crappies.”

Clarence attended Lincoln School for Colored Children. He remembered students “did a whole lot of reading, arithmetic, geography, and other things like track, basketball, and baseball. We didn’t have any White teachers”. When Clarence graduated from eighth grade at Lincoln, he started working at the Montgomery County Lumber Yard on Green Street in 1920. He began by sweeping shavings and moved to delivering materials to customers. “To be able to go to work, I had to go get my work permit. But I had to go to school as well as work. I said that if I didn’t get to play baseball or basketball, I wouldn’t go to school. The superintendent agreed that I could play”. Unfortunately, the athletic director disagreed and told Clarence, “No Niggers can play on my team.” Clarence punched him, knocked him down, broke his nose, and walked out. “The school was going to sue me, and then I was going to sue it; because they weren’t supposed to say “Nigger” in the school. He (the athletic director) was from the South, and none of the White people liked him. If White people don’t like someone of their own color, then you know that something is the matter.” Clarence stayed with the Montgomery County Lumber Company until it closed, selling the last piece of lumber from the business. With the money he made, he purchased his parents’ house.

Clarence was married three times. He married his first wife, Estella “Stella” Harriett James, in February 1929. Their son, Jasper Norwood, was born on 24 October 1936. However, Clarence sued for divorce on 19 January 1935. Clarence married his second wife, Augusta Pettus, in November 1942. They, too, divorced. He married again on 22 December 1955 to Lillian Dorothy Collier. The couple lived at 212 West Spring Street.

Clarence played semiprofessional baseball with multiple teams pitching, playing first base and centerfield. As he tells the story, “I played my first game when I was just nine years old. We were called the Crawfordsville Greys, a colored team. I was just a batboy when the centerfielder could not play. So they put me in centerfield. I ran, jumped the fence, and caught a flyball. I have played ball ever since”.

Clarence worked for Amtrak selling tickets, loading, and counting people. He worked as a chauffeur and custodian for the Ben Hur Building, Wabash College’s Goodrich Hall, and Phi Delta Gamma. He ran the skating rink, washed houses, and worked at the courthouse. He left the area in 1969 and worked for a doctor and as a chauffeur in the Danville area.

Clarence remembers the Ku Klux Klan meeting in about 1966 held on State Road 136, on top of the hill. “They were always talking about colored people; they were going to let them do this and that. At one time, all dressed in white clothes, they built a cross on this guy’s farm. Some of the White people and the colored people were going out to shoot him.” When asked about his thoughts on the Civil Rights Movement, Clarence said, “colored people are entitled to the same as the White people are because we serve the Lord first of all here on earth. It’s all in politics. You’re human, and everyone else is human.”

Relatives and Crawfordsville residents remember Clarence’s outstanding pool-playing skills that he honed on Indianapolis’ “The Avenue” (Indiana Avenue near the Walker Theater). He was so good that he was banned from the local Bank Cigar Store because he was labeled a pool shark.

Clarence died on 14 November 1985 and was buried in Oak Hill Cemetery